View the archive of my 90-minute class and discover the ways I’ve found that the process and progress of our lives – like Song – knows more than we do.

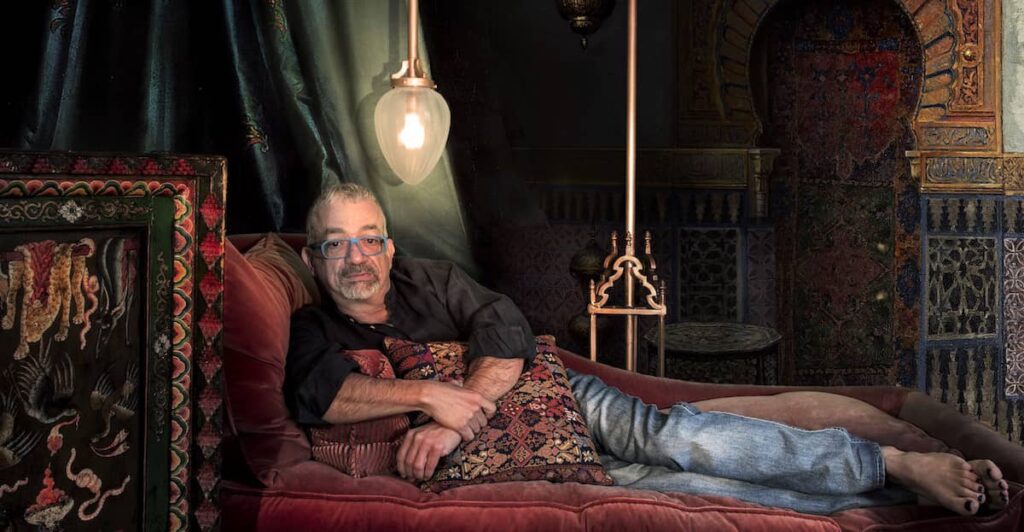

My name is Joe Henry. And for the uninitiated among you (please: no show of hands), I declare myself to be a songwriter, singer, and recording artist; a 3-time Grammy-winning record producer (oh, vanity!); a poet, essayist, and author.

I am also a devoted husband of thirty-four years and the father of two: neither fact incidental to who I am as an artist, or the way that I have evolved in that station.

. . . . .

My friend, the poet Jane Hirshfield, once acknowledged a fundamental truth I’d never before heard properly acknowledged, saying:

“The poem has an intelligence that the poet does not possess.”

Blessed be.

When she spoke this, I felt struck as an old tower bell is struck; felt both enlightened and liberated as an artist and as a man; for it has never not been my witness that I am led into thought – understand who I am and what I believe – by the songs that I have been writing since I was fifteen years old. And since those earliest year of having my ear to the street and my shoulder to the wheel, I know that more than anything, I have been cultivating, creatively-speaking, a surrender into process.

By this, I do not mean “surrender” in terms of resignation, but of radical acceptance.

By this, I do not mean that the “creative process” is limited to the making of songs or any other so-called Art; but rather it is as a habit of being; for as I work, so do I live.

And the longer that I live and the longer I have worked, I see that the line I first thought must separate the two has become blurred and ever-changing. Most everything of significance I have learned in my lifetime has either been ushered in on the arm of Song, or affirmed and made clear by it.

All this I mean to tell you when we are together.

All this I hope to make clear when cloudy, and to make blurry when clarity defeats true understanding – for so much of what we experience happens in shadow and thus must be spoken from there.

An outline for my time with you might look like this (though what follows cannot define the engagement any more than a paper map of a road can faithfully describe the storm and humanity you may encounter when upon it):

• Life is mysterious in nature; and we are called not to dispel mystery but to abide it; to stand in its weather, and be shaped by its shifting shape; to rejoice in all that is unseen and wholly / holy unknowable.

• No matter how solitary may be your methods, every creative endeavor is collaborative: a collaboration with time, experience, history, tradition, circumstance, expectation, desire, and breakfast, to name but a few.

•All of mortal living is defined by tension. In the way that no kite remains aloft without the tension of its tether, so no love exists without a taut string between us; and thus it can be plucked to sound, like the string of a guitar – resonate and melodic.

• Like Song, successful living as well as the loved that attends it are not defined by any notion of Perfection – for there is no such thing within mortal life. The mere fact of impermanence should liberate and invite all of us away from the exhausting abstraction of that desire and its false sense of control, and into acceptance, into surrender; away from self-expression and toward discover; into the moment wherein everything that Is feels to have been…inevitable.

• Was that five? I have one additional thing to include, and you may call it a bonus if, by then, it feels like one; and that is that courtesy of Song, I came to see the connective tissue between every-thing and all of us. I can point back and often do to the moment when, at about age ten, i first heard Bob Dylan. Suffice for this moment to say that Bob didn’t change everything as much as he unified everything. By peeling back the onion on his journey and process, I could hear the connection in all I was encountering: understood the taut thread (tension again) that stitched Hank Williams and Jimmy Reed to the so-called beat poets; Miles Davis, Picasso and Cassius Clay (as he was known in that moment of revelation) to Richard Pryor; Walt Whitman to Duke Ellington, and on to Orson Welles.

I’ll strive to share with you the ways in which I believe the process and progress of our lives – like Song, and like Jane’s aforementioned poem – thankfully, compassionately, with wonder and by grace…knows more than we do.

I hope you may join me.

Joe Henry

Bath, Maine