View the archive of our 90-minute class and discover the Five Things We’ve Learned about bringing international cinema to the American audience, about cinema’s rich history, and about the many ways to love the movies.

When I was about 10, while looking through the stacks in my local public library, I came upon a shelf labeled “Movies,”—793, I think, in the old Dewey Decimal System. Before me were half a dozen books on film. This seemed so strange to me—books about movies? Even though by then I was a pretty voracious filmgoer, somehow I didn’t quite imagine what a book about the movies could be. I checked one out, The Liveliest Art, by Arthur Knight, and soon was entranced. Knight traced the movies from shots of speeding trains to the glory days of Hollywood, also discussing the new waves of cinema coming from abroad. I began to note when some of the films he talked about would show up on TV.

Then, on a Sunday in early September, 1965, the advertisement for the Third New York Film Festival came out in the Times; scouring its offerings, I was amazed to find THE WEDDING MARCH by Erich von Stroheim, one of the more colorful characters in Knight’s book—“the man you love to hate”—and I knew his movies were really hard to see. I asked my parents if I could go and, after getting my wonderful, ballet-loving aunt to agree to accompany me, we ordered tickets. A few weeks later we were sitting in what eventually became Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center. A man came out to introduce the film; he was Henri Langlois, legendary Director of the Cinémathèque Française, although at that time I had no idea what that meant. The lights came down, the piano accompaniment started, and THE WEDDING MARCH lit up the screen. I was completely hooked.

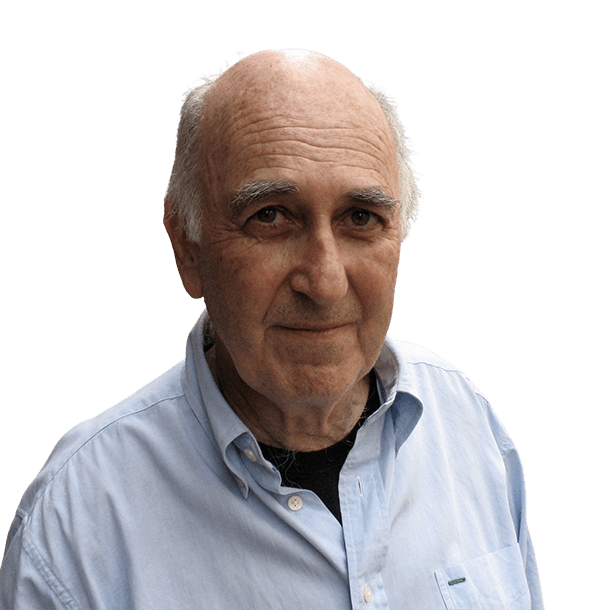

Somehow, 23 years later, I found myself on the stage of Alice Tully Hall, opening the Twenty-Sixth New York Film Festival as its director, a position I was privileged to have for the next twenty-five years. Simultaneously, I tried to keep up an academic career, and since 1989 I’ve been teaching film history and theory at Columbia University. When people ask what I do, I sometimes reply “I’m in the film history business.” As a programmer, I organized retrospectives of national cinemas and significant film artists; as a festival director, I got to cull a wide range of a given year’s films and come up with a kind of snapshot of where my colleagues and I thought the cinema was headed. And finally, as a film professor, I get to offer my thoughts on how the cinema has grown, adapted and evolved over its 125-year history, hoping whatever insights I offer can serve the next generation of filmmakers.

Another question I’m sometimes asked is “Can you still watch movies just for pleasure?” I can’t imagine how else one can watch a movie. If anything, I’m often disappointed that more people don’t take advantage of the enormous, voluptuous banquet the cinema is offering up — such a range of styles, themes, subjects, approaches — more than enough to delight and intrigue every viewer. Sadly, most seem satisfied with only the “fast food” offerings on display at our multiplexes or on our TV screens.

I’m delighted to have been asked to share with you my thoughts about cinema’s past, present and future, and it’s a special treat to be having this conversation with my dear friend Phillip Lopate — one of the few people I know whose passion for the adventure that is the cinema easily matches mine. I look forward to comparing notes on some cinema’s classic masters, and debate who our contemporary masters might be, as well as where we each think that the ”action” in cinema really is nowadays. The writing of film history, and especially film criticism, is an issue of special concern to both of us, and we’ll discuss what we look for when we read about film. As two avid filmgoers, I think both of us are concerned about what seems to be the incipient decline of theatrical screenings; we’ll compare predictions as to what the future of the movie theater could be. Finally, I’m sure there will be plenty of questions about my time at the New York Film Festival—what went right, what went wrong.

I very much hope you’ll join us.

I first fell in love with films when I was a little kid and my parents sent me and my siblings off to the local double-feature movie house so that they could have some “private time.” While they were engrossed in whatever that meant, I was drinking in the erotic magic of Veronica Lake and Yvonne DeCarlo doing their mischief onscreen. As a teenager I had the good fortune to be living through a cinematic high point (the French New Wave, the Italian masters Rossellini, Fellini, Antonioni, Satyajit Ray, the last flourishing of classical Hollywood masters like Ford, Hawks and Hitchcock, the American experimentalists Cassavetes, Mekas, Shirley Clarke…) I started a club in college called Filmmakers of Columbia, and made a short film, but regrettably my working class parents had little money to support my habit, unlike my classmate Brian de Palma whose father was a wealthy surgeon, so I put down my Bolex and turned to the typewriter instead.

Since then I have written some twenty books: essay and poetry collections, novels, monographs, edited anthologies. Not bragging, just saying. I’ve also written a ton of film criticism, because I’m still movie-mad. But the fact is that though I’ve written for the New York Times, Vogue, Film Comment, Cineaste, etc., I’ve never had an official critic’s post and remain something of an outsider in the world of film festivals. That’s why I was so grateful when Richard Peña asked me to serve on the New York Film Festival selection committee, along with “legitimate” critics. At the time, Richard and I were acquaintances, so I was surprised when he tapped me, but over the decades we have morphed into close friends. Part of that intimacy was acquired during the tricky process of agreeing on which films to include or exclude. Richard can be quite commanding, (dare I say bullying?) but I was never shy about standing up to and opposing him, if need be, which may have accelerated our warm friendship and certainly our mutual respect.

So now I get the chance to engage him in conversation about our mutual love of the cinema. Five seems a small number of the possible takeaways I am expecting from our talk, but I expect a few of the following to emerge. When we were young, barely more than kids, why did we think it necessary to learn the whole history of cinema? What was it like for Richard to assume the mantle of the Lincoln Center Film Society, and act not only as a film programmer but an administrator, a negotiator with foreign distributors, a multi-lingual presence on the global scene? How does he view the differences between our roles: I as a writer and film critic, he as a curator, scholar, all-purpose film maven? What does he think of film criticism–who are his favorite film critics? We have both ended up as professors at Columbia: what has been the impact of our teaching lives on our understanding of movies? How has our both being parents affected our sense of responsibility to pass down the knowledge of film history? How do we see the future of film, the current trends, the risks and problems? I am sure we will not run out of things to talk about, and I would welcome the comments of listeners and kibbitzers.

Please join us!